AD Cranbrook Architecture

Unprompted: Open-ended Investigations in the Choreography of Construction

The following is an excerpt from Cranbrook Architecture: A Legacy of Latitude.

About the Publication

The renowned Cranbrook Academy of Art near Detroit, Michigan, has been described as the epicentre of American Modernism. When it opened in 1932 it combined a stunning Eliel Saarinen-designed campus with a radically open educational philosophy to attract and produce some of the most influential artists, designers and architects in US history, including Charles and Ray Eames, Fumihiko Maki, Florence Knoll and Edmund Bacon. Often compared to other experimental schools such as the Bauhaus, Black Mountain College and Taliesin, Cranbrook’s sustained purpose has been advancing a wide, interdisciplinary latitude and self-directed design research to expand and diversify its approaches to architectural practice. There is a deep and persistent idea that open and experimental acts of making should define pedagogy, and by extension that education should shape practice, not the other way around. Cranbrook’s rigorous defiance of dogma and loose grip on the disciplines enables an educational model that combines the practices of art, design, making and urbanism. In this issue, alumni, faculty and scholars reflect on Cranbrook’s model in light of contemporary and challenging questions in architectural education, practice and the profession.

Contributors: Kevin Adkisson, Emily Baker, Peggy Deamer, Pia Ednie-Brown, Ronit Eisenbach, Dan Hoffman, Yu-Chih Hsiao, Peter Lynch, Bill Massie, Hani Rashid, Jesse Reiser, Lois Weinthal, and Tod Williams.

Featured architects: Asymptote Architecture, Building Culture PLA, Reiser+Umemoto (RUR), Studio Libeskind, and Tod Williams Billie Tsien.

Inventor, fabricator, architect and educator Emily Baker laments the rarity of open-ended architectural education that Cranbrook so exemplifies. She explains the bottom-up approach to design, material fabrication and use of emerging digital tools she developed while attending Cranbrook in the 2010s. She works at full scale and encourages her students to do the same.

Cranbrook has a mystique from the outside and can be as hard to pin down once inside. This nebulous nature is by design. Cranbrook Academy of Art contains one of the few instances of architectural education where truly open-ended inquiry is not simply available, it is the only option. Each student finds themself landed in a wilderness of ideas with no path out except by their own making. This is not to suggest that there has never been any zeitgeist within the school, because that would not be fully true. Even so, no one, including the department’s single faculty member, provides a prompt. This chance to stare into the void and then to act is a rare and valuable gift. It cultivates a particular type of creative individual, infused with questions that fill the following years and likely an entire creative life.

Questions to Build On

In 2010, I started in Cranbrook’s Architecture Department, then headed by Bill Massie, with some questions that arose from previous years in practice. I wanted to know how adaptations in the ‘choreography of construction’ – a term I began using after spending significant time observing construction sites – would impact both the structuring and the aesthetics of the buildings produced. One significant way that construction was poised to change was the proliferation of new fabrication techniques and digital processes. I thought of age-old construction systems – brick walls, thatched roofs, wood framing – all refined through use. Could new systems be derived and evolved to suggest new choreographies of construction, yet similarly tuned to materials, resources, human aptitude or even delight?

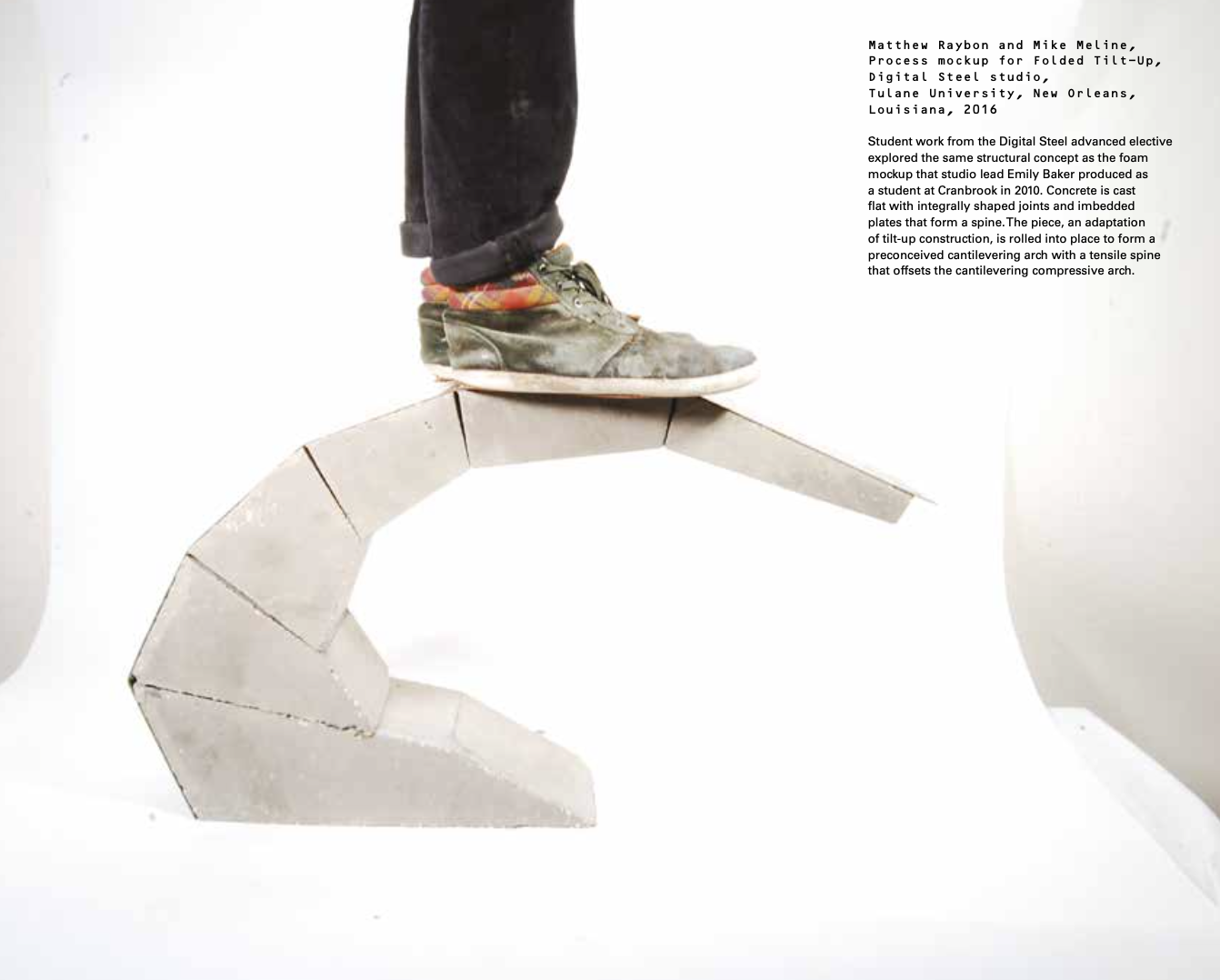

‘This time at school goes by quickly’, I was repeatedly told. ‘You need to know what you want to do while you’re there before you start.’ But the question of how to evolve construction did not conjure results in my mind. All I had were the actions I could take today, and the question they raised for tomorrow. (Not a metaphorical tomorrow, but the real one coming in a few hours.) In a programme absent of courses or curriculum, all that was left to do was make work and reflect on it. I knew I wanted to focus on constructed experimentation and little else. Through drawing and writing, ideas formed, and I started to make objects. I imagined, for example, how adapting concrete-reinforcing with computational fabrication could suggest new structural configurations and choreographies of construction, and thus new aesthetics. Constructed studies such as a crude yet dynamic assembly of foam and paracord revealed a possible system of cantilevering arches and the beginnings of a formal and aesthetic language I would later call FoldedTilt-Up. Each quick-and-dirty study precipitated a more refined one, a larger one, a serial one of a specific joint, or an experiment with a new material process. Beginning with the end in mind may have benefits, but if you know too well how you want to end, then you are not on a path to discovery.

One of the discoveries I made while at Cranbrook became my thesis work, the kirigami space-frame system Spin-Valence, which was exhibited in the grounds of the Cranbrook Art Museum in 2012 and is now part of its permanent collection. It would be easy for me to depict the development of Spin-Valence as an inevitable result of clear motivations, but the real story is meandering and disjointed. Could I have arrived at this system, in which individual units are cut into continuous sheet material and pushed out of the surface to reconnect in a parallel plane, producing a structural lattice from a single folded part, in a more efficient manner if only I had laid out the problem more clearly? No. I did not set out to make a space-frame system, nor was it the only compelling idea I found as I sought choreographies of construction enabled by digitally cut steel. I needed to make a plethora of mockups and mistakes, have my intuition thwarted often, and fail, rather than succeed (as the adage ‘begin with the end in mind’ would encourage) as early as possible to reveal that which would refine the work and become a path of inquiry.

Elegant Interconnection

My questions from my studies at Cranbrook coalesced into a design approach that I cultivated as I began teaching and furthering my creative practice. Construction using digital processes seemed more often employed as a top-down methodology — the whole (often a non-normative geometry) conceived ahead of the details that make it up. My reverse approach of starting with a material/ process pairing to develop systems for construction that might then suggest a whole to later be parametrically informed, led me into relatively unexplored territory. I believe this route is more akin to the way many of our ubiquitous building systems have been created, refined then aestheticized – through use, and tuned by the hands of builders.

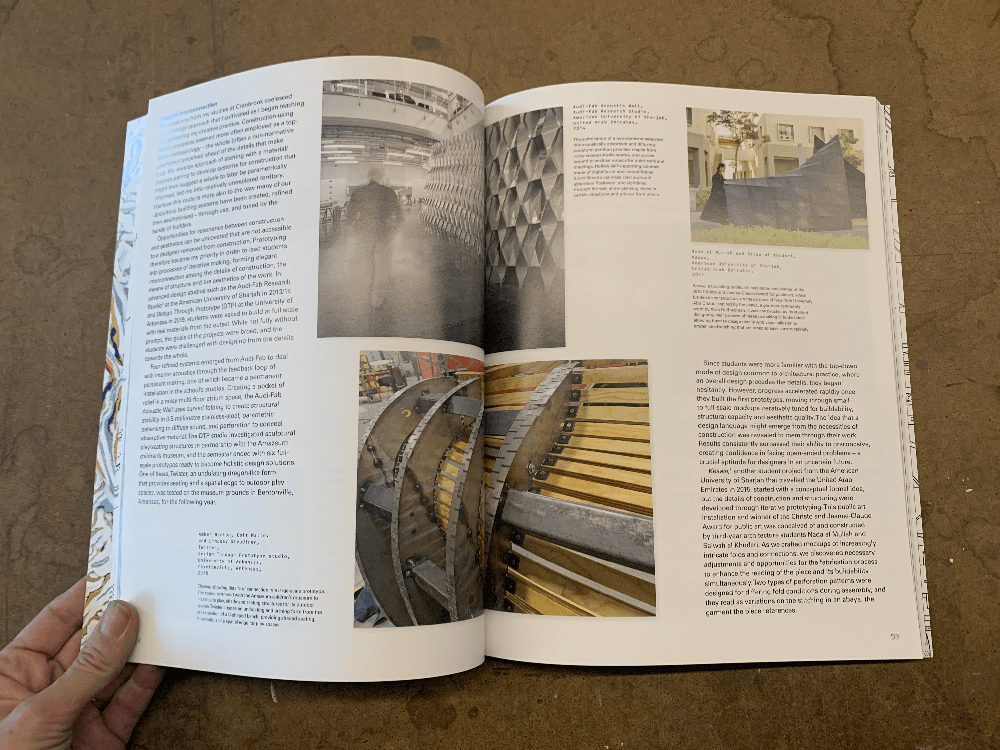

Opportunities for resonance between construction and aesthetics can be uncovered that are not accessible to a designer removed from construction. Prototyping therefore became my priority in order to lead students into processes of iterative making, forming elegant interconnection among the details of construction, the means of structure and the aesthetics of the work. In advanced design studios such as the Audi-Fab Research Studio at the American University of Sharjah in 2013/14 and DesignThrough Prototype (DTP) at the University of Arkansas in 2019, students were asked to build at full scale with real materials from the outset. While not fully without prompt, the goals of the projects were broad, and the students were challenged with designing from the details towards the whole.

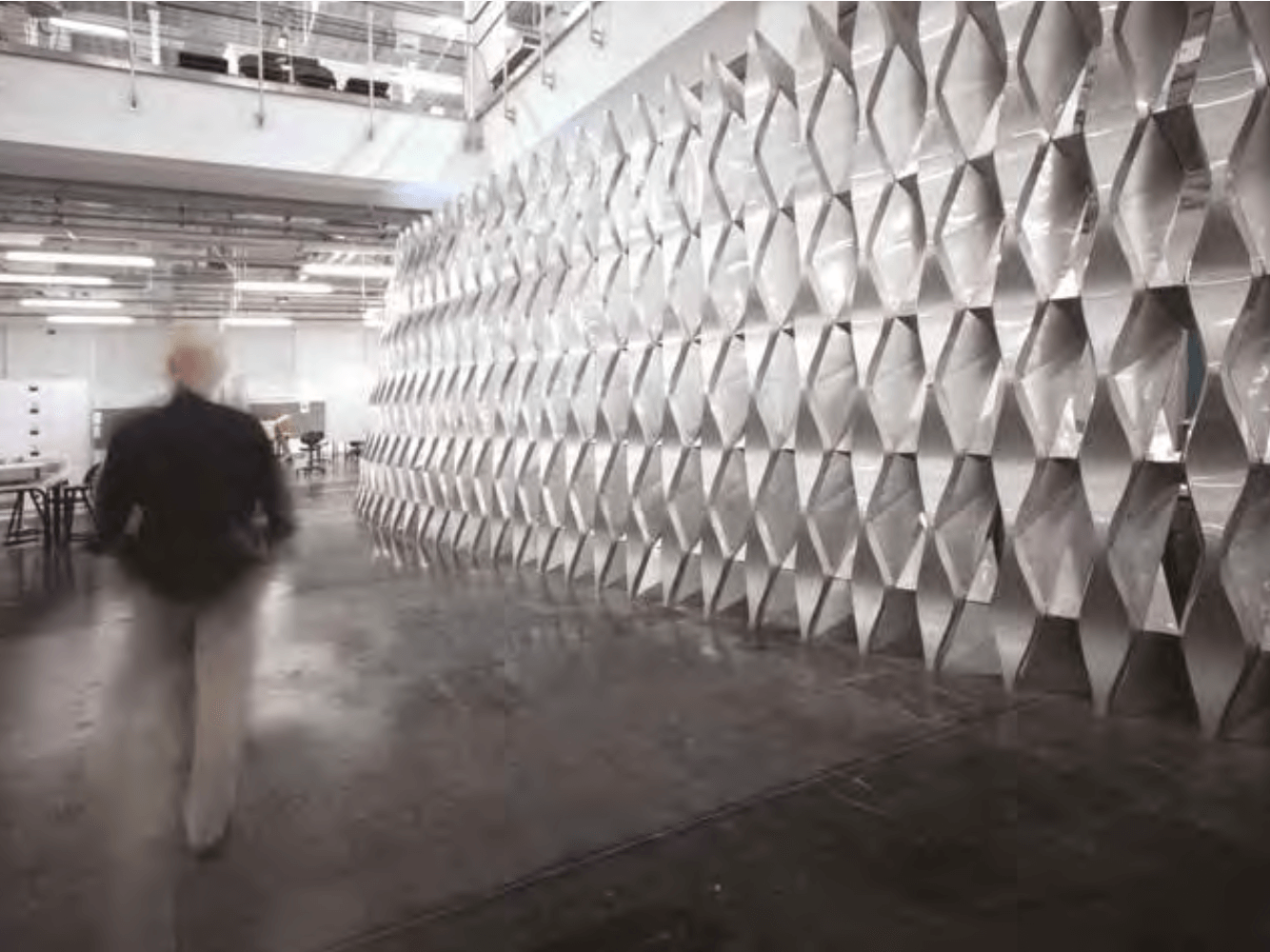

Four refined systems emerged from Audi-Fab to deal with interior acoustics through the feedback loop of persistent making, one of which became a permanent installation in the school’s studios. Creating a pocket of relief in a noisy multi-floor atrium space, the Audi-Fab Acoustic Wall uses curved folding to create structural stability in 0.5-millimetre stainless-steel parametric patterning to diffuse sound, and perforation to conceal absorptive material. The DTP studio investigated sculptural play/seating structures in partnership with the Amazeum Children’s Museum, and the semester ended with six full-scale prototypes ready to become holistic design solutions. One of these, Twister, an undulating dragon-like form that provides seating and a spatial edge to outdoor play spaces, was tested on the museum grounds in Bentonville, Arkansas, for the following year.

Since students were more familiar with the top-down mode of design common to architectural practice, where an overall design precedes the details, they began hesitantly. However, progress accelerated rapidly once they built the first prototypes, moving through small to full-scale mockups iteratively tuned for buildability, structural capacity and aesthetic quality. The idea that a design language might emerge from the necessities of construction was revealed to them through their work. Results consistently surpassed their ability to preconceive, creating confidence in facing open-ended problems – a crucial aptitude for designers in an uncertain future.

Keswa, another student project from the American University of Sharjah that travelled the United Arab Emirates in 2015, started with a conceptual formal idea, but the details of construction and structuring were developed through iterative prototyping. This public art installation and winner of the Christo and Jeanne-Claude Award for public art was conceived of and constructed by third-year architecture students Nada al Mullah and Salwah al Khudari. As we crafted mockups of increasingly intricate folds and connections, we discovered necessary adjustments and opportunities for the fabrication process to enhance the reading of the piece and its buildability simultaneously. Two types of perforation patterns were designed for differing fold conditions during assembly, and they read as variations on the stitching in an abaya, the garment the piece references.

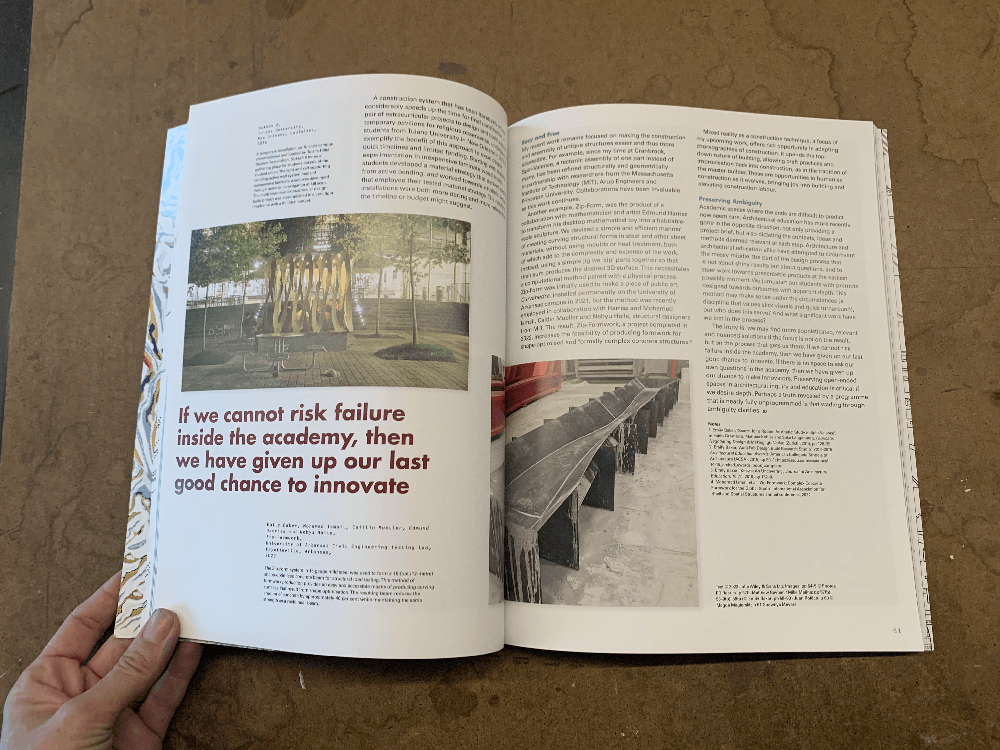

A construction system that has been iteratively refined considerably speeds up the time for final construction. A pair of extracurricular projects to design and build Sukkahs, temporary pavilions for religious observance, undertaken by students from Tulane University in New Orleans in 2017/18, exemplify the benefit of this approach to excel despite quick timelines and limited funding. Starting with material experimentation in inexpensive laminate wood sheets, students developed a material strategy that derived stability from active bending, and worked towards a holistic design that employed their tested material strategy.The resulting installations were both more daring and more refined than the timeline or budget might suggest.

“If we cannot risk failure inside the academy, then we have given up our last good chance to innovate”

Easy and Free

My recent work remains focused on making the construction and assembly of unique structures easier and thus more accessible. For example, since my time at Cranbrook, Spin-Valence, a tectonic assembly of one part instead of many, has been refined structurally and geometrically in partnership with researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Arup Engineers and Princeton University. Collaborations have been invaluable as this work continues.

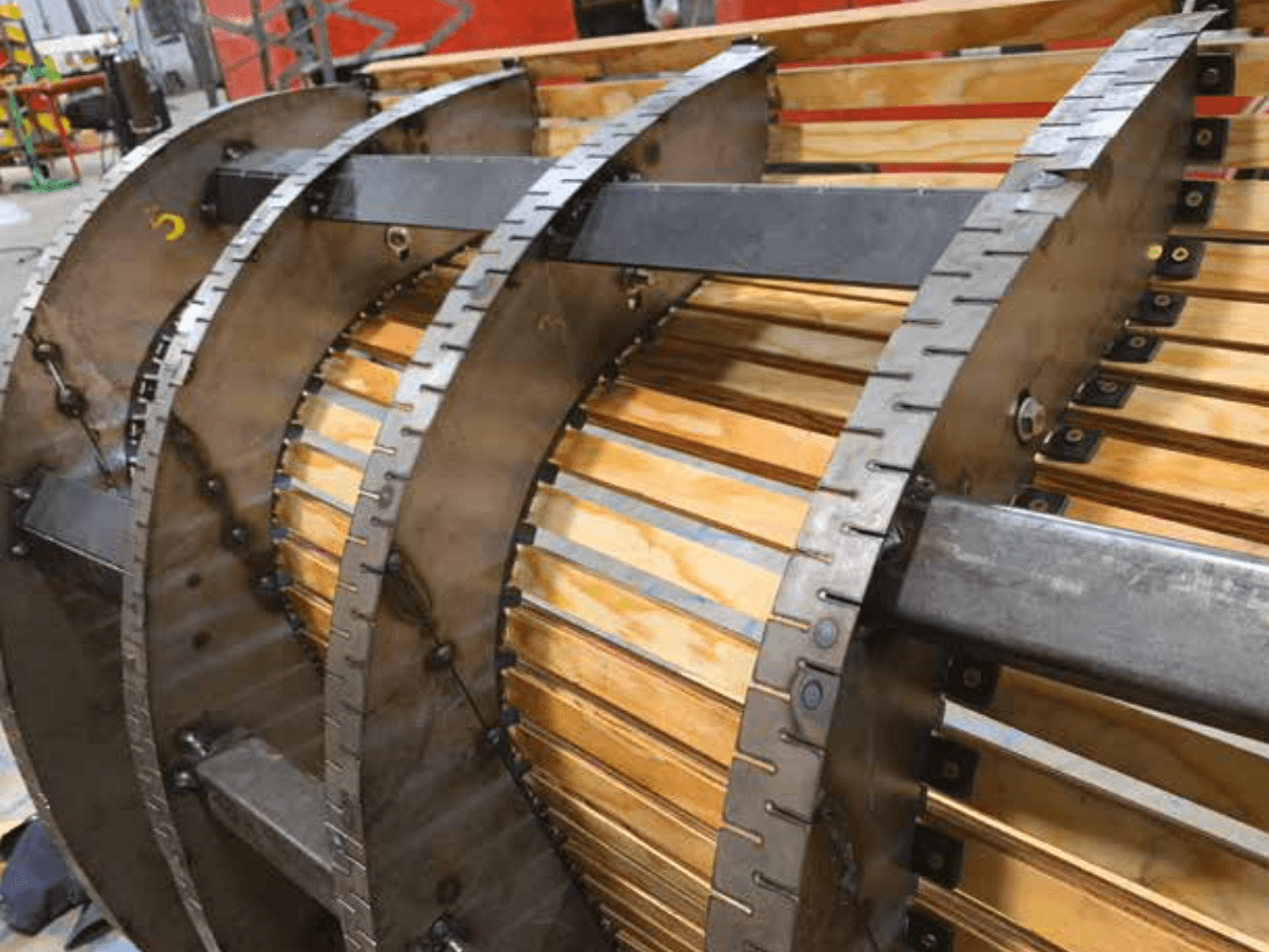

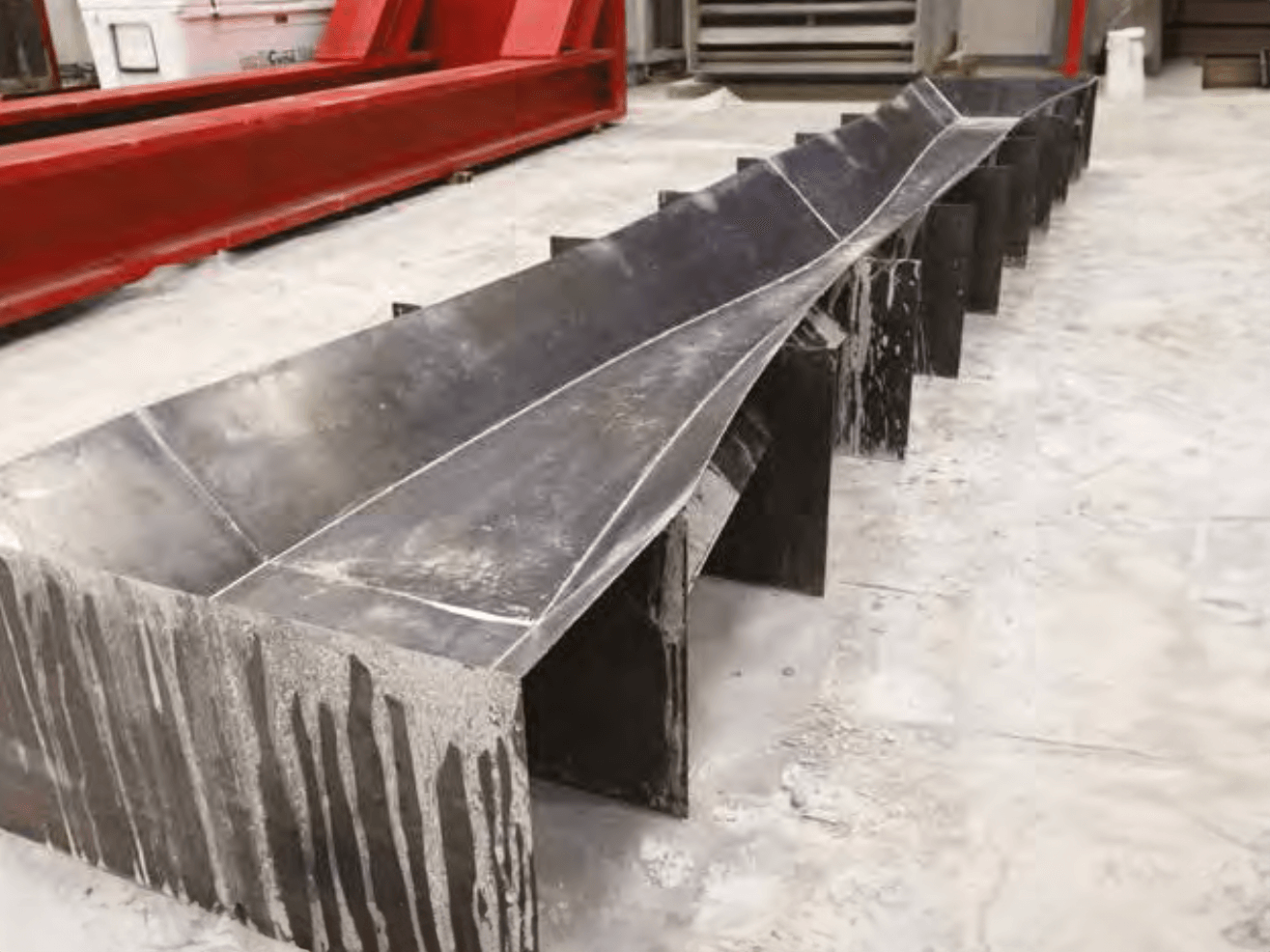

Another example, Zip-Form, was the product of a collaboration with mathematician and artist Edmund Harriss to transform his desktop mathematical toy into a habitable-scale sculpture. We devised a simple and efficient manner of creating curving structural forms in steel and other sheet materials, without using molds or heat treatment, both of which add to the complexity and expense of the work. Instead, using a simple jig we ‘zip’ parts together so that their sum produces the desired 3D surface. This necessitates a computational method paired with a physical process. Zip-Form was initially used to make a piece of public art, Curvahedra, installed permanently on the University of Arkansas campus in 2021, but the method was recently employed in collaboration with Harris and Mohamed Ismail, Caitlin Meuller and Nebyu Haile, structural designers from MIT. The result, Zip-Formwork, a project completed in 2022, increases the feasibility of producing formwork for shape-optimized and formally complex concrete structures.

Mixed reality as a construction technique, a focus of my upcoming work, offers rich opportunity in adapting choreographies of construction. It upends the top-down nature of building, allowing craft practices and improvisation back into construction, as in the tradition of the master builder. These are opportunities to humanise construction as it evolves, bringing joy into building and elevating construction labour.

Preserving Ambiguity

Academic spaces where the ends are difficult to predict now seem rare. Architectural education has more recently gone in the opposite direction, not only providing a project brief, but also dictating the contexts, ideas and methods deemed relevant at each step. Architecture and architectural education alike have attempted to circumvent the messy middle, the part of the design process that is not about shiny results but about questions, and to steer work towards presentable products at the earliest possible moment. We jumpstart our students with prompts designed towards outcomes with apparent depth.This method may make sense under the circumstances (a discipline that values slick visuals and quick turnaround), but who does this serve? And what significant work have we lost in the process?

The irony is, we may find more sophisticated, relevant and nuanced solutions if the focus is not on the result, but on the process that gets us there. If we cannot risk failure inside the academy, then we have given up our last good chance to innovate. If there is no space to ask our own questions in the academy, then we have given up our chance to make innovators. Preserving open-ended spaces in architectural inquiry and education is critical if we desire depth. Perhaps a truth revealed by a programme that is nearly fully unprogrammed is that wading through ambiguity clarifies.